3 Submission Management Systems for Literary Journals: an Overview

While the days of mailing self-addressed, stamped envelopes (along with typed or laser-printed poems, short stories, or short creative non-fiction) to journals are not completely behind us, it's become increasingly rare to find a literary journal that does not use cyberspace as a way of accepting submissions. Today, in fact, when one talks about a submission system being “old fashioned” or “low-tech,” chances are pretty good that that means email! More and more literary magazines today are leaving even email submissions behind, instead using submission management systems to track authors and their writing, including updates on which editors have read what so far and whether staff members have voted to accept or reject the work.

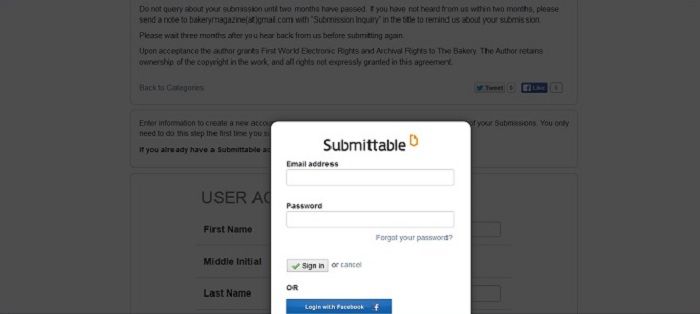

Submittable

By now, editors and aspiring writers alike have certainly encountered the user-friendly interface of the open-source software of Submittable (formerly called – and often still referred to as – “Submishmash”). Authors who click the “submit” button on the websites of journals that use Submittable recognize the pop-up form that's branded with the company's familiar orange logo. Submittable is used not only by some of the most well-known and prestigious journals like The New Yorker, McSweeney's , and The Atlantic – but it's also what a large percentage of respected journals that are not as well known outside of the literary world are using, too.

From the editorial side, Submittable has been called a “one-stop shop,” allowing for automatic emails to be sent to authors, acknowledging receipt of submissions – and also allowing editorial staff to easily rank submissions and track information. The Submittable website also boasts that no web designer is needed to use the system, and submission capability can be built into a journal's existing site. Submittable is PCI compliant and secure – and it also allows for analytics, reporting, and the exporting of data. Editors can review submissions on their iPads, iPhones, or Kindles.

There are 3 Submittable plan levels, costing from $220 to $2200 per year, depending on the number of editorial staff who will be accessing the account, as well as the number of submissions the system will be able to handle. However, non-profits and/or publishers of art or literature get a 50% discount with the coupon code “NonProfitArtLit .” And, speaking of the issue of money, Submittable also allows journals to collect reading fees.

One Submittable features writers appreciate is that a Submittable username (the user's email address) and password, once set up for one literary magazine, is good for logging in to all journals with submissions systems powered by Submittable. They may also appreciate the fact that authors, whenever they're logged in from any Submittable-subscribing journal's website, will see a complete list of work submitted to other Submittable journals as well, along with a note on what's accepted, rejected, or still simply “in progress.”

Submission Manager

Writers who submit their work to journals that don't use Submittable may often experience a strange feeling of déjà vu when clicking on a literary magazine's “submit” button and finding themselves being asked to create an account on a vaguely familiar-looking grid page. There's a reason for this feeling of déjà vu: sign-up and log-in pages powered by another popular literary journal submission management system – going simply by the name “Submission Manager” – does, unfortunately, require writers to create a new account for each journal; despite the familiar-looking user interface and the feeling that you've “been here before,” the déjà vu often just means you've submitted work to another journal that uses Submission Manager – but not yet for this particular journal (meaning, yes, you do have to create a new account).

Submission Manager's website boasts that it manages reading periods – which means that neither authors nor editors have to face the annoyance of trying to submit work (or of getting work) during a time when editors are not accepting it. It also allows the capability, where an SMTP application is available, to send automatic emails that acknowledge submissions. Submission Manager consists of a MySQL (version 4.1 or higher) database with a front end programmed in PHP (version 4.3 or higher). It requires a web server and a browser that's set up to accept cookies. While there's no eye-catching logo like the memorable orange one that Submittable uses, the color scheme and fonts can be customized.

Most marketing for Submission Manager seems to be through the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses (CLMP), a non-profit organization which is funded in part by the National Endowment for the arts – and which offers Submission Manager's services to literary journals for $200.

Tell it Slant

A third submission management option for literary journals is Tell it Slant. One feature that Tell it Slant predominantly markets is how it handles simultaneous submissions; like Submittable (and unlike Submission Manager), Tell it Slant allows authors to use a single username and password – when logging in either from individual literary journal websites or directly from Tell it Slant's own site. This particular submission management system, however, goes a step farther, also taking full advantage of having all information together in one place – by first detecting when a single piece of writing has been submitted to more than one journal that uses Tell it Slant; then, when one journal on the system accepts the simultaneously submitted piece, that piece of writing is automatically deleted from the submission queues for other journals on the system. This is great news not only for journals but also for authors, who usually have to go through and individually withdraw the accepted piece of writing from consideration by other journals.

Tell it Slant also boasts of forum-style discussion capability that allows editors to have meaningful online exchanges about specific submissions and authors – as well as a function that allows editors to perform keyword searches in author bios. A handy feature for writers is that there's also a specific area of the user profile that builds this bio – whereas, with other sites, adding biographical information tends to be a matter of authors having to copy-and-paste their bios in from elsewhere every time they submit work.

Their site is free for literary journals, with processing fees being charged only for submissions to journals that receive more than 75 a month submissions a month. The processing fee also applies for journals which charge a reading fee.

As far as payment information is concerned, from the writer's perspective, authors who submit their work purchase “credits” through PayPal in order to pay submission fees when using the system. According to Tell it Slant's website, prices vary by journal but tend to be between $1.50 and $3.00.

While it is true that many journals using Submittable and Submission Manager, by contrast, don't charge submission fees, it's worth noting that submitting to journals the the old-fashioned way (through the U.S. Postal Service) requires sufficient postage for sending the writing (costing more or less, depending on the size of the manuscript), plus a self-addressed stamped envelope for a reply (and an additional amount of postage when authors want to have the manuscript returned to them) – all of which adds up for any writer trying to get their work out there. According to Tell it Slant's website, their credit system was started with the plan of eventually offering discounts for writers who buy credits in bulk, so they're making an effort to really make this fee system worth everyone's while.

Check out Tell It Slant

Writers and literary journal editors alike today appreciate the ways in which technology has helped to streamline the editorial process. While email is easier to search and track than the old-fashioned paper-and-envelope method, many literary magazine editors have embraced the multitude of features that submission management systems offer. Submitting writers, too, appreciate the seamless, paper-free systems that more journals are using now; with any luck, the fact that more writers are able to get out of the post office line – and get online instead – also means they're able to spend more time crafting great work that's one step closer to being discovered.